Contrary to the popular song, the neck bone is actually connected to one of 22 separate head bones that make up the human skull. These plate-like bones intersect at specialized joints called sutures, which normally allow the skull to expand as the brain grows, but are absent in children with a birth defect called craniosynostosis. A new study in Nature Communications presents a detailed cellular atlas of the developing coronal suture, the one most commonly fused as a consequence of single gene mutations. The study brought together scientists from the laboratories of Gage Crump, Robert Maxson, and Amy Merrill at USC, and the laboratories of Andrew Wilkie and Stephen Twigg at the University of Oxford.

“Named for its location at the crown of the head, the coronal suture is affected in a number of birth defects,” said lead author D’Juan Farmer, a postdoctoral fellow in the Crump Lab. “These infants and children have to undergo a series of invasive and dangerous surgeries to expand their skulls, and we wanted to understand why the coronal suture is particularly sensitive to gene disruptions. So with an aim toward advancing new interventions for patients, we created the first detailed cell-by-cell description of how this suture develops.”

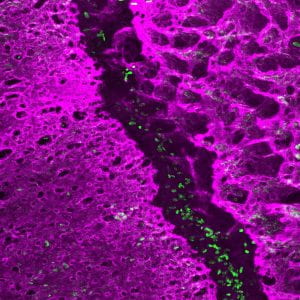

To achieve this, Farmer and his collaborators isolated cells from the developing coronal sutures of mice. The team then used sophisticated new DNA sequencing techniques to catalog the activities of all the protein-coding genes in thousands of individual cells.

To read more, visit https://stemcell.keck.usc.edu/coronal-suture.